Where the Wild Things Are

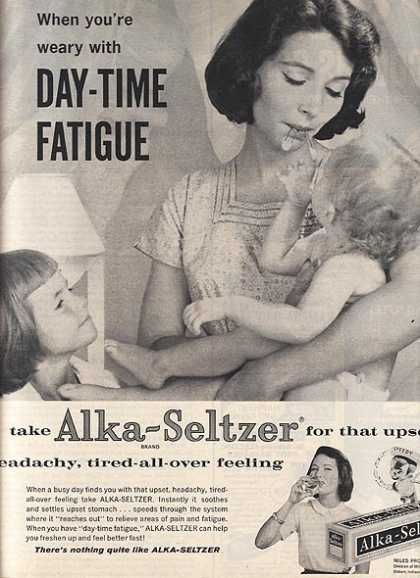

Like most people, I grew up hearing stories about my parents’ childhoods. There was plenty of ‘I walked ten miles to school every day, through four feet of snow, up hill, BOTH WAYS,’ and ‘We used to get REAL spankings, with a BELT.’ Though sometimes bored, I was offered a picture of a wholesome, simpler time, a place where you could call home with just a dime, men were men, and women weren’t allowed personal bank accounts.

My mother’s stories were of the ‘I had one pair of socks, which were hand-washed and hung to dry every night’ variety. She shared tales of the family’s worn furniture, the shame of their raggedy, holy clothes, and of ‘playing’ in their backyard, which was simply a cement plot. They didn’t enjoy exotic foods like oranges.

These conversations inevitably led to her gesturing around wildly. We were expected to pause and take in the splendor of our middle class home, stocked to the brim with multiple pairs of socks, fancy foods like canned chop suey and Jiffy muffin mix, and stockings filled with oranges at Christmas. We were royalty compared to the squalor from whence she came. “I mean, look at all of these television sets!” she’d proclaim.

My dad’s stories were also riddled with poverty. No holiday was complete without the heartbreaking retelling of the year he received just one tiny gift, and how the kids at school painfully ridiculed him for treasuring the trinket. He would mist up a little, dab at his eyes, and make a quiet remark about how lucky we all were. We were always left feeling spoiled and undeserving, but also angry. How dare these playground twats we’d never met ruin our nice day? I would stew angrily, daydreaming that the bullies lived out their days pumping gas in impoverished mining towns, developing meth addictions that rendered them toothless and unable to feel joy.

I digress. My dad’s stories were also littered with what every hungry kid really wants: adventure. His family moved often, including one family caravan to the desert of Arizona, a place filled with snakes and scorpions. While we moved as much if not more than a military family, it was always just around Michigan. They had five kids, whereas we only had two. He spoke of driving motorcycles, hitchhiking across the country, learning how to play guitar, sleeping on beaches, and almost dying lost in the desert AND Lake Michigan.

Upon seeing the film ‘Stand By Me,’ I suspected I was getting a fictional taste of my father’s adventurous youth. As the four boys set off down the tracks to find that body, I was reminiscent for a youth I’d never experienced. How I longed to stumble upon a body, or even just a hand or a leg.

And while I still haven’t come across any body parts (a simple finger or toe was really too much to ask for, Universe?) I’ve come to realize my childhood was more adventurous than anything my own kids could ever hope for.

The essential list of ‘items to keep in one’s pockets’ in ‘The Dangerous Book for Boys‘ includes such essentials as a flashlight, a compass, and a pencil and paper, all of which are rendered obsolete by the ever-present cellphone. Which really isn’t even a consideration, when you take into account that we no longer let our kids out of our sight. Even at the age of ten, we only let K go to the end of the block, and that’s with friends and supplies and a very stern talking to before leaving the house. I say things like ‘IF EVEN ONE ADULT IS AT THE PARK COME HOME IMMEDIATELY,’ ‘DON’T FORGET YOUR HAND SANITIZER,’ and ‘YOU DON’T HAVE TO TALK TO ANYONE – IF SOMEONE SAYS HELLO YOU CAN SCREAM AND RUN BACK TO THE HOUSE.’

I distinctly remember walking to and from school in the second grade, easily a mile one way, and I was responsible for my younger brother. When the older, scary kids were behind us, we’d find a reason to jump into the bushes and ‘explore’ until they were gone. Sometimes a weary mom from the apartment complex would take pity and let us climb onto the pile of nine children in the back of her sedan. More than once a door didn’t get latched before takeoff, and we’d all scream, pulling an errant child back into the car before a corner was rounded and a foot was clipped off by the door’s swift closure. The mom would flick her cigarette out the window and shout back at us, “Jesus Christ, quit fooling around!’

‘Window seats’ were reserved for the stalwartly, like myself. I longed to get tossed out of a car, or forgotten at a market, or attacked by a loose animal at the zoo. The unaccompanied traversing of suburbia was ok, but I wanted more.

And I’m sure my children long for adventure also. I see how they push each other down flights of stairs, watch scary movies, and jump off of the back deck, an act which will certainly be put to a stop when someone finally breaks an ankle. But let’s be honest: they’re sheltered from actual danger. Do they realize it? I’m not sure. But part of me pities the adventurer surely living within them all. Without knowing the terror of being lost in a busy shopping mall and having to find security to page your furious parent, what even IS childhood?

I brought this up to the teens, using the lack of actual adventure and danger, the resourcefulness it calls for, as an explanation for the anxiety and depression currently so prevalent. But their eyes glaze over. Conversations about my exciting childhood earn me that look generally reserved for Christmas dinners when Grandma starts asking after aunts and uncles no longer with us. ‘Poor Mom,’ that look says. ‘Sometimes she has moments of clarity. Other times she waxes philosophical about the joy of hunting for edible berries in the woods when you’re seven and locked out of the house.’ Tongue click.

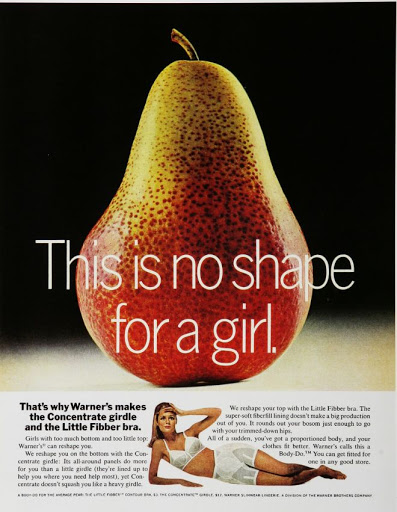

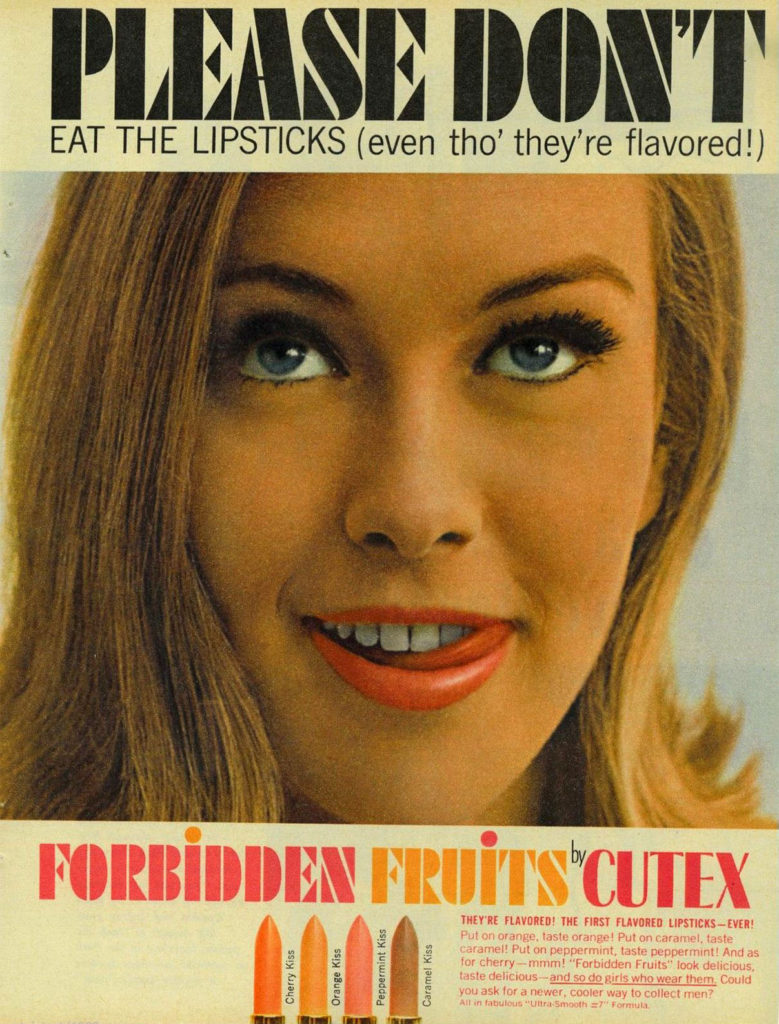

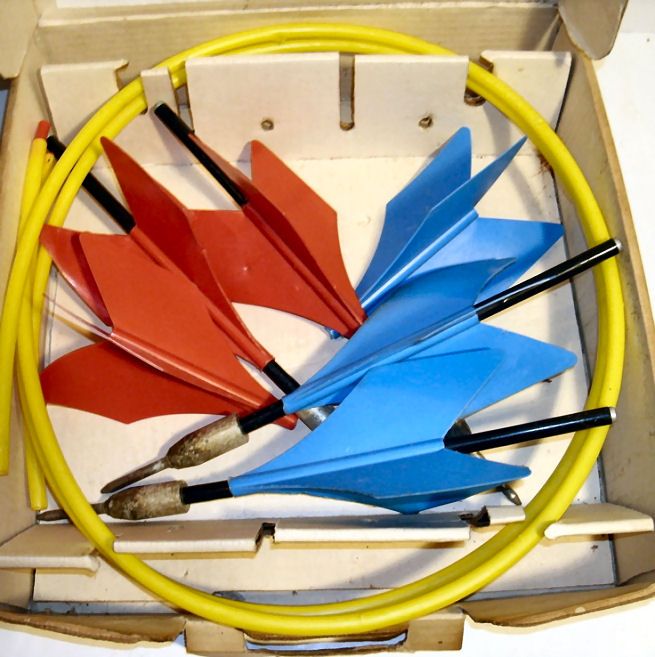

But this is raising kids today. No bike riding without helmets, no lawn darts, no merry-go-rounds. The most dangerous thing my kids do is eat fruit snacks that aren’t certified organic. And I feel bad for them. The same way I felt bad for myself growing up, never having the opportunity to hitchhike, because by the early 90’s there were one too many Datelines about how that could turn out.

To take risks is sublime. I want to give my kids the gift of embracing fear and uncertainty, of recognizing the joy in stepping outside of a comfort zone and into unknown territory. Get IN that scary cab! Drink that milk two days past expiration! Drive after the gas light comes on! (Sorry, honey. I know you hate that one.)

Though I was always fed, and kept (mostly) safe, I’m glad I was able to taste a bit of the wild life. I’d like to think that lawn dart to the chest those few times made me stronger, and that processed chicken patties and orange sodas opened my palate to the struggle food that got me through my early twenties. Maybe I’ll take the net around the trampoline down, just to give my poor kids at least a taste of danger.